Recorded by: Klaus Lüber

“I feel as if I have been robbed of my language”

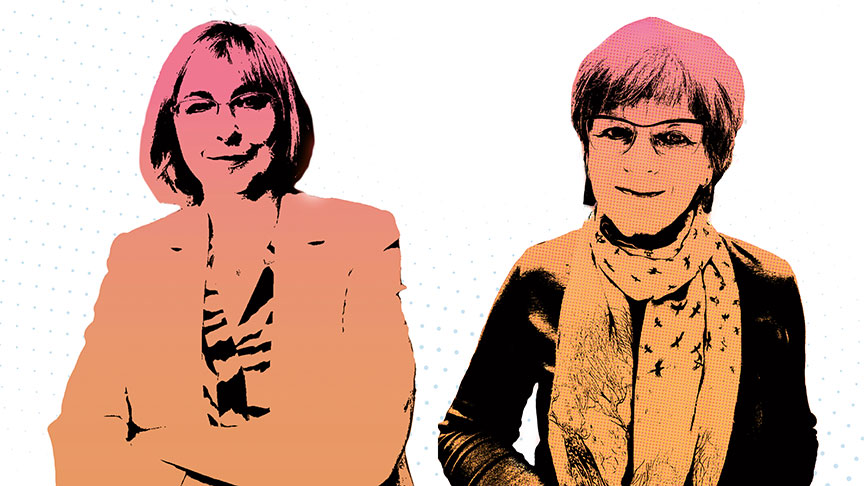

What role does language policy play in Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine? A dialogue between Alla Paslavska from Lviv and Lilia Besugla from Kharkiv, Ukrainian Germanists, DAAD alumnae and university professors who are both currently working at German universities.

Lilia Besugla: When we consider the role that language plays in the current war in Ukraine, I feel it is important first to dispense with one dangerous narrative that Russian propaganda has been spreading for some time. Namely the claim that Ukrainian is in fact nothing more than a dialect of Russian. But that is not the case at all. Ukrainian and Russian differ considerably, both in their written forms and in their pronunciation. The differences are at least as pronounced as those between French and Italian. Ukrainian is much closer to Polish and Czech than it is to Russian.

Alla Paslavska: Russia has always attempted to deny Ukrainian’s existence as a language in its own right. This is a centuries-old story that began during the Russian Empire when reading primers, church records, religious services and school lessons in Ukrainian were banned, and in the Soviet Union later involved the extermination of numerous Ukrainian writers and artists. The russification of all the peoples of the Soviet Union was one of the regime’s key objectives. In 1990 for example I myself was forced to do my PhD in Lviv (Western Ukraine) in Russian because there was no other option. Most newspapers and almost all programmes broadcast on television and radio were in Russian. That wasn’t a natural process, it was political coercion.

Lilia Besugla: Yes, that is a very important point. In 2001, during the only census in independent Ukraine to date, only 30 percent of Ukrainians stated that Russian was their mother tongue. I myself gave my native language as Ukrainian at the time, despite, just like you, Ms Paslavska, having in actual fact been socialised almost entirely in Russian – from nursery school to university. My parents spoke Ukrainian, however, a language I knew from my childhood. So for me it was quite clear that Ukrainian was my mother tongue, even though later my mother herself always spoke Russian with me.

Alla Paslavska: My experience was almost exactly the same. There can be no doubt that Russian was imposed on people as an instrument of political power. This is obvious from the mere fact that everyone in Ukraine understands and speaks Ukrainian and Russian, whereas virtually nobody in Russia speaks Ukrainian.

“Ukrainian and Russian differ considerably, both in their written forms and in their pronunciation.”

Lilia Besugla: Language definitely plays a key role in the current war. A war prepared by the propaganda long before the first military conflicts. I am from Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine, where certain words and phrases kept creeping into everyday Russian usage well before hostilities first began in 2014. They were especially created by Russian propaganda with the intention of dividing the population. Take for example 9 May 1945, the day of victory over Nazi Germany. In Ukrainian we commemorate this day with the slogan “Never again” (Ніколи знову!), while in Russian it became standard practice to declare “We can do it again” (Можем повторить!). A simple linguistic analysis would reveal that in such contexts Ukrainian is dominated by set phrases that push more for peace and the defence of our country, whereas in Russian they tend to be more about aggression.

Alla Paslavska: And that is why it comes as no surprise that backlashes against the Russian language have increased massively since Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2014, and especially after 24 February 2022. And this despite the fact that Russian had an objectively higher status than Ukrainian for a long time. In 1989, a law gave Russian the status of the language of “interethnic communication”, and in 2012 Russian was defined as the “regional language”. It was only when the 2019 Language Act was adopted and gradually implemented that genuine conditions were established for Ukrainian to achieve its status as the sole state language, as enshrined in Ukraine’s constitution.

Lilia Besugla: I believe that was exactly the right thing to do. I cannot understand the criticism that is sometimes expressed, namely that this is tantamount to banning the Russian language. In my view, that is nothing but propaganda. It is about promoting national identity, of which language is an important part. And obviously Ukrainian plays a key role in this context. This is something that the war has made abundantly clear to us once again. I know many people who now make a point of speaking Ukrainian in their daily lives. My daughter, for example. She speaks Ukrainian to her husband, and when I speak to her in Russian, she replies in Ukrainian.

Alla Paslavska: I also know many similar examples. One can really say that the war has given us another push as far as our sense of our own language and identity is concerned. Nonetheless, I would not wish to overemphasise the role that language played in the outbreak of war. It is important now not to make any mistakes in terms of language policy. After all, we are at war – a war that makes everything and everyone cruel. Language per se cannot be blamed for being instrumentalised by politicians. But we just have to accept that we are at war. And the wounds that are being inflicted on our country every day by Russia and in Russian are deep, cost many human lives and will take time to heal. Many Russian-speaking Ukrainians are deliberately switching to Ukrainian in their everyday lives. The Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov, who writes in Russian, said recently in an interview that he will not be able to write in Russian for as long as Russia’s war against Ukraine persists.

Lilia Besugla: As far as I am concerned, Russia is indeed the language of the enemy just now, as the Ukrainian author Alexander Kabanov put it in 2017. I really feel at the moment as if I have been robbed of my language.

Alla Paslavska: That is entirely understandable from your perspective. After all, you are a poet yourself and have spent your entire life writing in Russian.

Lilia Besugla: That’s true. And now I can no longer write in Russia but my Ukrainian isn’t good enough yet.

Alla Paslavska: But you already did a very good job on the translation into Ukrainian of the poet Mascha Kaléko that you recently presented at a symposium in Hanover.

Lilia Besugla: Thank you, dear Ms Paslawska. It is truly something of a personal tragedy for me that I can no longer write in Russian and my Ukrainian isn’t yet as good as I would like. And as it perhaps would have been if the language had enjoyed a higher status in my childhood and youth. That is why I wanted to get some practice in this way.

Did you take part in the most recent radio dictation on 9 November, by the way? It’s been held for over 20 years now to mark the day of Ukrainian Writing and Language and has really become something of an event. Unfortunately I missed it myself.

Alla Paslavska: Yes, I did take part though I have to admit that I made a lot of mistakes. Later, however, I found out that nobody completed it without any this year. There is still much to be done in terms of cultivating the Ukrainian language, in other words.

Professor Lilia Besugla teaches German philology and translation in Kharkiv and is a DAAD alumna. She fled to Germany when the Russian air strikes on the Eastern Ukrainian city began. Since April 2022 she has been a visiting researcher at the Institute for German as a Foreign Language and Intercultural Studies at the University of Jena.

Professor Alla Paslavska runs the Department of Intercultural Communication and Translation at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. A DAAD alumna, she is also president of the Ukrainian Association of German Teachers and German Studies. Currently she is teaching as a visiting professor at the Department of German and Comparative Studies at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU).